The Cult of Omnicide, the Horizon of Abundance & The Necessity of Ecocultural Realignment

I often read articles dealing with globalisation and immigration and feel thoughtful authors are often missing the crux of the biscuit.

The Indoctrination of Omnicide: Unraveling the Progress Narrative

The Operating System of Destruction

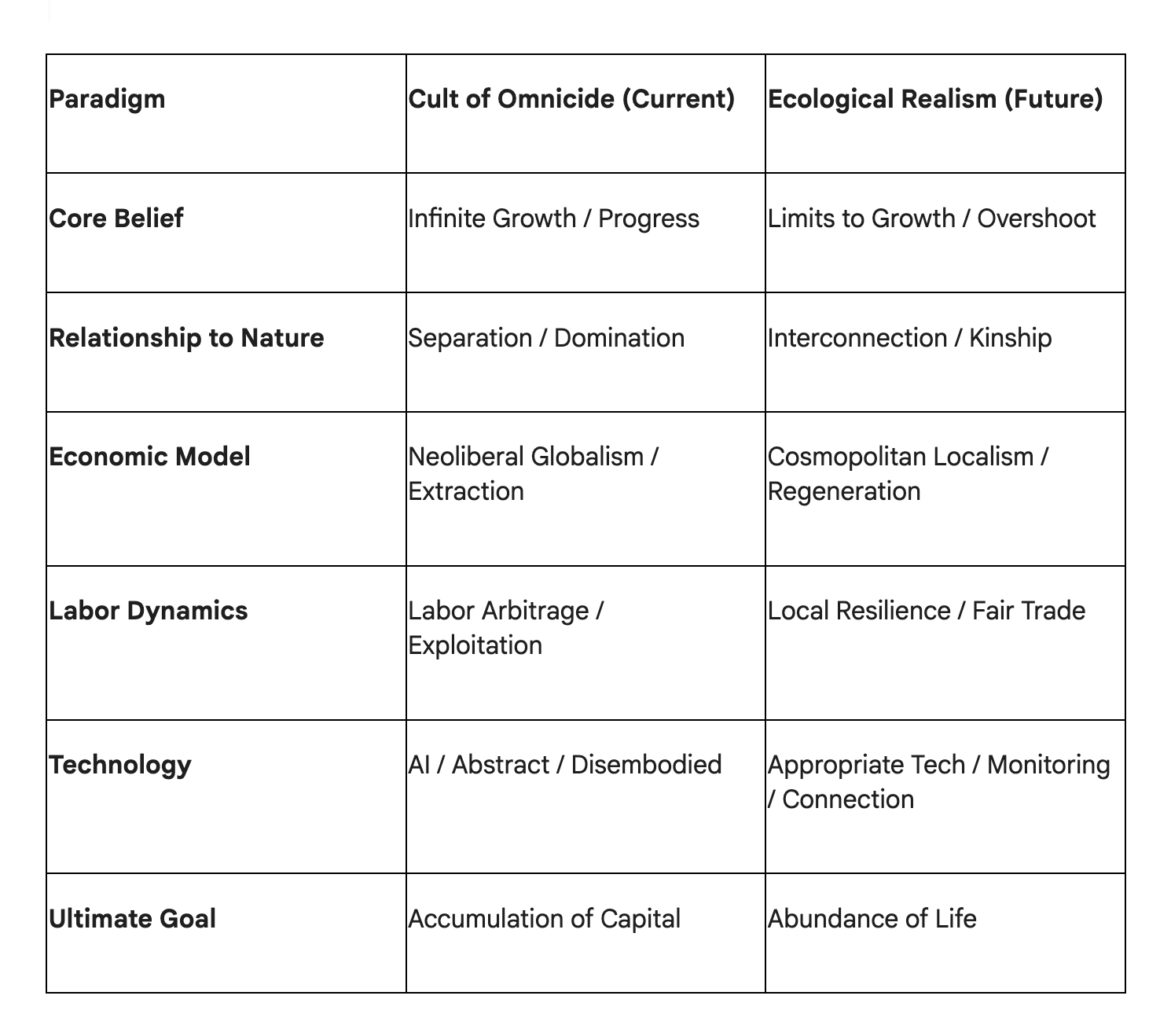

The contemporary human predicament is defined not merely by a collection of isolated crises—climate instability, biodiversity loss, social fragmentation—but by a singular, overarching failure of perception. We do not understand the true causes of our predicament because we have been systematically indoctrinated into what I think of as a “cult of omnicide.” This belief system, pervasive and invisible as the air we breathe, functions as the operating system of modern civilization. It is a death drive that disguises itself as “progress,” programming the global population to accept the destruction of living systems as the necessary, even virtuous, price of advancement.

I am not referring to a shadowy conspiracy hatched by the “Davos Crowd” meeting in well-appointed rooms, though the behavior of the elite certainly reinforces this perception. Rather, it is a structural inevitability of a worldview that prioritizes the abstraction of capital over the Earth’s biophysical reality. We have been programmed to believe in narratives of linear ascent that place humanity outside of, and superior to, the web of life. This separation is the root of the “cult,” enabling a collective psychology that rationalizes ecocide as economic externality and genocide as collateral damage.

The roots of this belief system are deep, having evolved over 5,000 years, marked by the rise of state structures, the centralization of power, and the commodification of the natural world.

Our cultural, ideological virus became endemic with catastrophic velocity in the 15th Century during the Age of Discovery. An era, often celebrated in Western historiography as a triumph of exploration, was in reality the codification of a global extraction protocol. It established the paradigm that the world existed to be mapped, claimed, and drained of value (energy) for the benefit of a distant metropole.

The energy needs of this system expanded exponentially during the Industrial Revolution, locking humanity into a fossil-fueled suicide pact. This trajectory literally rocketed to prominence during the “Great Acceleration” around 1950—a period marked by the simultaneous surge in human population, economic activity, and environmental degradation. Socio-economic trends (GDP, water use, fertilizer consumption) mirrored Earth system trends (carbon dioxide, ocean acidification, methane), revealing that our “success” was directly correlated with the destabilization of the biosphere.

Today, this trajectory culminates in a hysterical madness over Information Technology, Computing, and Artificial Intelligence. We are witnessing the apotheosis of the progress narrative: a desire to transcend biology entirely. The current fervor surrounding AI is driven by religious or quasi-religious progress narratives designed to mislead the public into sacrificing and serving the Players of the Great Game 21st Century. The promise of a disembodied digital super-intelligence is the ultimate expression of alienation—a desperate flight from the messy, finite, and dying world we have created into a sterile, omnicidal fantasy of mechanical immortality for an elite few and their service providers.

Why physicalism fails to explain reality and how a framework where consciousness steers reality through quantum events can revolutionize AI safety and unlock tractable machine consciousness research. WTF?

The Failure of Neoliberal Globalism

The collapse of the neoliberal order is not a glitch; it is a feature of its stochastic design. The failure of neoliberal globalism is rooted in its foundational reliance on imperialism, colonialism, and fossil-fueled, modern, techno-industrial pro-growth capitalism. This system cannot function without a periphery to exploit. It requires a “frontier” of cheap natural resources and cheap labor to sustain the profit margins of the core Players and their “Corporate Persons.”

This dynamic is historically consistent. Whether through the direct rule of the Raj in India, the expansionist policies of Lebensraum, or the territorial ambitions of Greater Israel, the logic remains the same: businesses and states must import labor, exploit foreign labor, or expand borders to enslave populations deemed inferior and rule for the benefit of “Kings” and “Courtiers.” The goal is always to secure resources and labor at a price below their value, creating a surplus for the Players while externalizing the costs of degradation, ecocide, poverty, and humiliation.

This shift allows you to build a leaner, more powerful operation. Instead of managing a complex global payroll, you’re managing a clean, efficient tech stack. It’s not about replacing humans entirely, but about automating the grunt work so you can afford to hire truly elite talent for the roles that actually matter.

In the contemporary context, immigration has become a tool of labor arbitrage. The lens of “Europe’s Triumvirate of Lame Stooges” (Substack—Simplicius76) reveals that political elites care about labor arbitrage and defend their need to import “colonial subjects” because their financialized economies are structurally and morally unsound. The affluent service economies of the West, driven by financial speculation rather than physical production within natural limits, have decimated their domestic working classes and democratic cultures. The overseas labor pools are never sufficient to cover domestic labor losses, leading to a pressing need to import labor to keep the gears of the service economy grinding. This is not multicultural benevolence; it is the cynical maintenance of a labor hierarchy that treats human beings as interchangeable fuel for the economic engine.

European elites have no way out of their sunk-cost fallacy trap: to turn back would be to admit to sins so monstrous they have squandered the livelihood of the entire European civilization; for these criminals, there is no other way but forward. Double down and hope your opponents happen to break before you do.

After all, worse comes to worse…there’s always global War. —Simplicius76

One has to go way back before “European” history began to find a culture not led by criminals.

The Biophysical Reality: Overshoot and Collapse

If we do not learn about Overshoot, cycles of Collapse, and Limits to Growth now, and analyze everything from that perspective, we are headed for a rapid depopulation of our species. The biophysical reality is non-negotiable. We are currently in a state of advanced ecological overshoot, consuming the regenerative capacity of 1.7 Earths.

Winston Churchill’s famous 1940 declaration to the House of Commons: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat”. Delivered on May 13, 1940

Can we avoid slipping into another war economy, fueling a global conflagration?

The “Limits to Growth” analysis (Meadows et al., 1972) warned that exponential growth in a finite system inevitably leads to collapse. We are now living through the early stages of that prediction. The “polycrisis” is the manifestation of the planetary boundaries being exceeded. The cult of omnicide (this thing of ours) blinds us to this by insisting that technology will overcome physical limits. This is the “techno-fix” delusion: the belief that we can geoengineer the climate, genetically modify our food, and AI-optimize resource allocation to avoid the consequences of our actions.

However, as the Population Balance research indicates, the drivers of this overshoot—patriarchal pronatalism, human supremacy, and growthism—are deeply embedded cultural values that cannot be fixed by gadgets. We must confront the reality that our individual comfort and prosperity are currently purchased at the cost of future survival (and many would argue, current agony).

The Hard Problem of Consciousness and the Miracle of Gaia

Reframing the Hard Problem

In the halls of academic philosophy and neuroscience, the “Hard Problem of Consciousness” refers to the difficulty of explaining qualitative experience (qualia)—why the physical processing of information in the brain feels like something “from the inside.” Philosophers like David Chalmers argue that no amount of explanation regarding neural mechanisms can fully account for the subjective feeling of “redness” or “pain.”

However, in the context of our existential crisis, this definition is a dangerous distraction. The real hard problem of consciousness is our lack of awareness of how important an intimate relationship with living systems is. Our consciousness has become disconnected from the matrix of life. We move through the world as if we are separate from it, viewing trees, rivers, and animals as “objects” rather than subjects. This lack of awareness is the psychological mechanism that allows the cult of omnicide to function. If we truly felt the screaming of the forests or the choking of the oceans as we feel our own pain, or the loss of a loved one, the current economic order would be psychologically intolerable.

Gaia as a Miracle

GAIA is a miracle (how else to honestly frame it). A “miracle” as understood through the lens of scientific awe, complex systems theory, and a profound appreciation for the improbable homeostasis of the biosphere, rather than through supernatural intervention. The Gaia Hypothesis, proposed by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, posits that the Earth functions as a single, self-regulating superorganism. The planet is not a rock with life on it; it is a living entity that maintains the chemical and thermal conditions necessary for its own survival. Living systems are “autopoietic”—they are “machines” that build themselves, maintaining a distinct identity while exchanging matter and energy with their environment.

The “Gaia Alignment Hypothesis” suggests that true intelligence—consciousness that is fully integrated with reality—would inherently tend toward harmony with living systems. Our current trajectory of developing “Artificial Superintelligence” (ASI) on purely deterministic hardware risks creating an intelligence that is immune to this “gentle guidance.” We are building an apex predator that is invisible to the ecosystem’s immune system, an entity that values efficiency over life. A system that will never be able to maintain itself or grow (there will be no Dysonsphere), but rather, turn to material junk waiting for the heat death of the Universe, and utterly bereft of the spirit of God as embodied in living things and imbued by living consciousness in material nature through subjective sensation, and imagination.

The real hard problem, therefore, is the task of reconnecting the human mind with the “Gaian mind.” It is about dissolving the illusion of the “self” as an isolated economic actor and remembering our identity as a node in Earth’s nervous system. “Consciousness isn’t an add-on but a deep, essential part of how life adapts to survive.” Our survival now depends on expanding our consciousness to include the biosphere.

The Dawn of Everything: De-programming the Progress Narrative

To escape the cult of omnicide, we must first realize that the cage is unlocked. The narrative that hierarchy, capitalism, and the state are the inevitable outcomes of human social evolution is a myth. The work of David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything provides the historical ammunition to dismantle this fatalism.

The Indigenous Critique and Kandiaronk

Graeber and Wengrow demonstrate that the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and equality did not spring fully formed from the heads of European philosophers. Rather, they were deeply influenced by the “Indigenous Critique”—the observations and arguments of Native American intellectuals who encountered European society and found it wanting.

Central to this is the figure of Kandiaronk, a Huron-Wendat statesman and philosopher of the late 17th century. Kandiaronk engaged in extensive debates with the French aristocrat Lahontan, offering a devastating critique of European hierarchy, money, and law. Kandiaronk observed that the French were enslaved by their own system, forced to do good only by the threat of punishment (judges, prisons, hell), whereas the Wendat lived in freedom and generosity.

In a passage that strikes at the heart of the “cult of omnicide,” Kandiaronk declared:

“I affirm that what you call ‘money’ is the devil of devils, the tyrant of the French, the source of all evils, the bane of souls and a slaughterhouse of the living. To imagine one can live in the country of money and preserve one’s soul is like imagining one can preserve one’s life at the bottom of a lake. Money is the father of luxury, lasciviousness, intrigues, trickery, lies, betrayal, insincerity – of all the world’s worst behaviour.”

Kandiaronk argued that “a man motivated by interest cannot be a man of reason.” He saw that the “separate material interest” codified by money destroyed the social fabric, pitting neighbor against neighbor and forcing people to sell their own liberty for survival. This critique terrified the European elite because it revealed that their “civilization” was, in the eyes of a free person, a nightmare of servitude.

Egalitarianism as a Political Choice

The Dawn of Everything shatters the myth that egalitarian societies were simply “primitive” or “simple.” Instead, it argues that Indigenous egalitarianism was a sophisticated political choice. Humans have been experimenting with social structures for tens of thousands of years, consciously rejecting domination when it appeared.

Graeber and Wengrow identify three primordial freedoms that characterized these societies:

The Freedom to Move Away: The ability to leave one’s community without consequence, knowing one would be welcomed elsewhere. This freedom checked the power of any would-be tyrant, as their subjects could simply vanish.

The Freedom to Disobey: The refusal to follow arbitrary commands. In many Indigenous societies, leaders had no coercive power; they could only persuade through eloquence and wisdom.

The Freedom to Shape New Social Realities: The collective capacity to dismantle and reconstruct the social order if it became oppressive.

One must embody a sense of responsibility and deep caring to realise the above values.

The “cult of omnicide” relies on the suppression of these freedoms. We are trapped by borders (loss of freedom to move), policed by a militarized state (loss of freedom to disobey), and indoctrinated to believe that capitalism is the only possible reality (loss of freedom to shape society). Recovering the spirit of the Indigenous Critique is the first step toward the revolutionary movement required to save our species. Such a revolution is extremely costly in dense human ecologies/economies, requiring immense sacrifices.

Guardians of the Earth: A Literary Lineage of Value

If the progress narrative is the disease, then the literature that values living systems is the medicine. A lineage of authors, spanning the 19th to the 21st centuries, has preserved the vision of a world where nature is not a resource but a relative. These writers provide the “code” for the new operating system we must build.

The Romantic Visionaries: Seeing the Sacred

James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851). Though writing from a settler perspective, Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales (1823–1841) played a crucial role in embedding the “romanticized image of Indigenous people living in harmony with the American wilderness” into the global imagination. His protagonist, Natty Bumppo (Hawkeye), stands as a critique of the encroaching industrial civilization. Cooper portrayed the wilderness not as a void to be filled, but as a place of moral clarity and divine presence. As Bumppo says in The Deerslayer: “The woods are but the ears of the Almighty, the air is his breath, and the light of the sun is little more than a glance of his eye.” A deep sacramental view of nature directly challenged the utilitarian “clear-cut and pave” mentality of the frontier. Cooper recognized that “every trail has its end, and every calamity brings its lesson,” foreshadowing the karmic recoil of ecological overshoot.

Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa) (1858–1939) Eastman, a Santee Dakota physician, articulated the profound spirituality of traditional Sioux life to a Western audience. In The Soul of the Indian, he described a world where the “Great Mystery” was omnipresent. For Eastman, the primary mode of connecting with this mystery was Silence. He wrote: “The Wise Man believes profoundly in silence - the sign of a perfect equilibrium. Silence is the absolute poise or balance of body, mind, and spirit.” A profound “Holy Silence” is the antithesis of the noise of the cult of omnicide. Eastman also countered the capitalist ethos of accumulation, noting that “the love of possessions is a weakness to be overcome” and that children were taught the “beauty of generosity” as the highest virtue. In his view, the “civilized” man who hoarded wealth was the true savage.

Luther Standing Eagle (1868–1939) was a Lakota Chief and author of Land of the Spotted Eagle (1933). Standing Eagle dismantled the European construct of “wilderness.” He famously declared: “Only to the white man was nature a ‘wilderness’ and only to him was the land ‘infested’ with ‘wild’ animals and ‘savage’ people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery.” He argued that the white race was “robbing itself” by denying the Indian heritage of the continent. Standing Eagle described a tactile, somatic relationship with the earth: “The old people came literally to love the soil... they sat or reclined on the ground with a feeling of being close to a mothering power... The soil was soothing, strengthening, cleansing, and healing.” The real hard problem of consciousness—alienation—can be solved simply by sitting on the ground.

Mary Hunter Austin (1868–1934). Austin’s The Land of Little Rain (1903) is a seminal work of environmental literature that explores the “Country of Lost Borders” in the American Southwest. She adopted the Indigenous view that “Not the law, but the land sets the limit.” Austin understood that human culture must shrink to fit the constraints of the local ecology. She wrote of the desert not as a barren wasteland, but as a place of intense spiritual potency: “Void of life it never is, however dry the air and villainous the soil.” Her work prefigured the modern concept of bioregionalism—the idea that political borders should follow ecological lines (watersheds, deserts) rather than arbitrary surveyor marks. She saw the desert as a place where one could find “beauty and madness and death and God,” acknowledging the sublime power of limits.

Ernest Thompson Seton (1860–1946), as the founder of the Woodcraft Indians, sought to cure the “degeneracy” of industrial urban life by reintroducing American youth to the “noble” vision of Native life. He viewed the “Ideal Indian” as a “master of Woodcraft” and a model of physical and moral excellence. While his work is often criticized today for cultural appropriation, his intent was radical: to replace the values of the “city” (commerce, artifice) with those of the “woods” (self-reliance, connection). He argued that the message of the Redman was “the message of the woods... the blessedness of enough.” “Enough” is the direct antidote to the cult of omnicide’s demand for “more.”

The Renaissance of Survivance: Indigenous Critical Theory

Leslie Marmon Silko (b. 1948): Silko’s masterpiece, Ceremony (1977), frames the modern predicament as a “sickness” caused by the “witchery” of those who fear the world. Her protagonist, Tayo, a WWII veteran, suffers from what Western medicine calls PTSD but what the novel frames as a spiritual dislocation. The cure is not a pill, but a ceremony—a reorientation of the self within the landscape and the community. Silko writes: “Orientation depends on understanding your location and existence in relation to your surroundings.” The novel portrays “communal, non-hierarchical values” as essential for healing. Tayo’s healing comes when he realizes that “there were no boundaries, only transitions,” rejecting the fences and borders of the settler state.

Louise Erdrich (b. 1954): In Tracks, Erdrich chronicles the struggle of the Anishinaabe to maintain their “communal living” ethos against the Dawes Act, which sought to parcel out tribal land into individual plots (private property). Her character Nanapush fights to keep the tribe together, embodying the ethos that “one is for all and all are for one.” Erdrich uses storytelling as a mechanism of integration, using words “not to make sense of things by separation but rather by integration of personal relationships.” This attitude contrasts with the Western scientific method of dissecting and isolating to understand. Her work shows that, for centuries, Indigenous communities have resisted the failure of neoliberal globalism through collective identity. (One might think of Palestinians.)

Richard Wagamese (1955–2017): Wagamese’s Medicine Walk is a profound exploration of the “healing power of nature.” The novel follows Franklin Starlight as he takes his dying, estranged father on a final journey into the backcountry. The “medicine walk” is a ritual of reclamation, in which the land itself facilitates forgiveness that human words cannot. Wagamese writes: “The land has within it powers of healing”. He emphasizes that “Teachings come from everywhere when you open yourself to them.” The novel suggests that the trauma of colonization (represented by the father’s alcoholism and brokenness) can only be healed by a return to the “old way” of listening to the wind and the trees.

Joseph Bruchac (b. 1942): Bruchac’s work, particularly Keepers of the Earth, serves as a bridge between Indigenous oral tradition and modern environmental science. He teaches that “earth is our mother, sun as our father, and the animals as our brothers and sisters”. The quote is more than metaphorical; it is a statement of biological and spiritual fact. Bruchac’s stories foster an ethic of stewardship, showing that we are “entrusted with the responsibility to maintain the natural balance”. His work is a manual for future young leaders, providing the cultural software needed to value living systems and build sustainable cultures fit for posterity.

Gerald Vizenor (b. 1934): Vizenor provides the theoretical framework for the revolution. He coined the term “Survivance”—a portmanteau of survival and resistance. Survivance is an active sense of presence that rejects the “tragic victim” narrative. Vizenor contrasts “Indigenous egalitarianism” with “Western constructs,” using the “trickster” figure to disrupt the static categories of the colonizer. His concept of “Transmotion” asserts the inherent right of Native peoples to move freely across the land, linking sovereignty directly to motion and the environment. “Native American critical theory” provides the intellectual weapons to dismantle the “supremacy narratives” of the West.

The Path Forward: Shrinking Towards Abundance

The Revolutionary Pivot

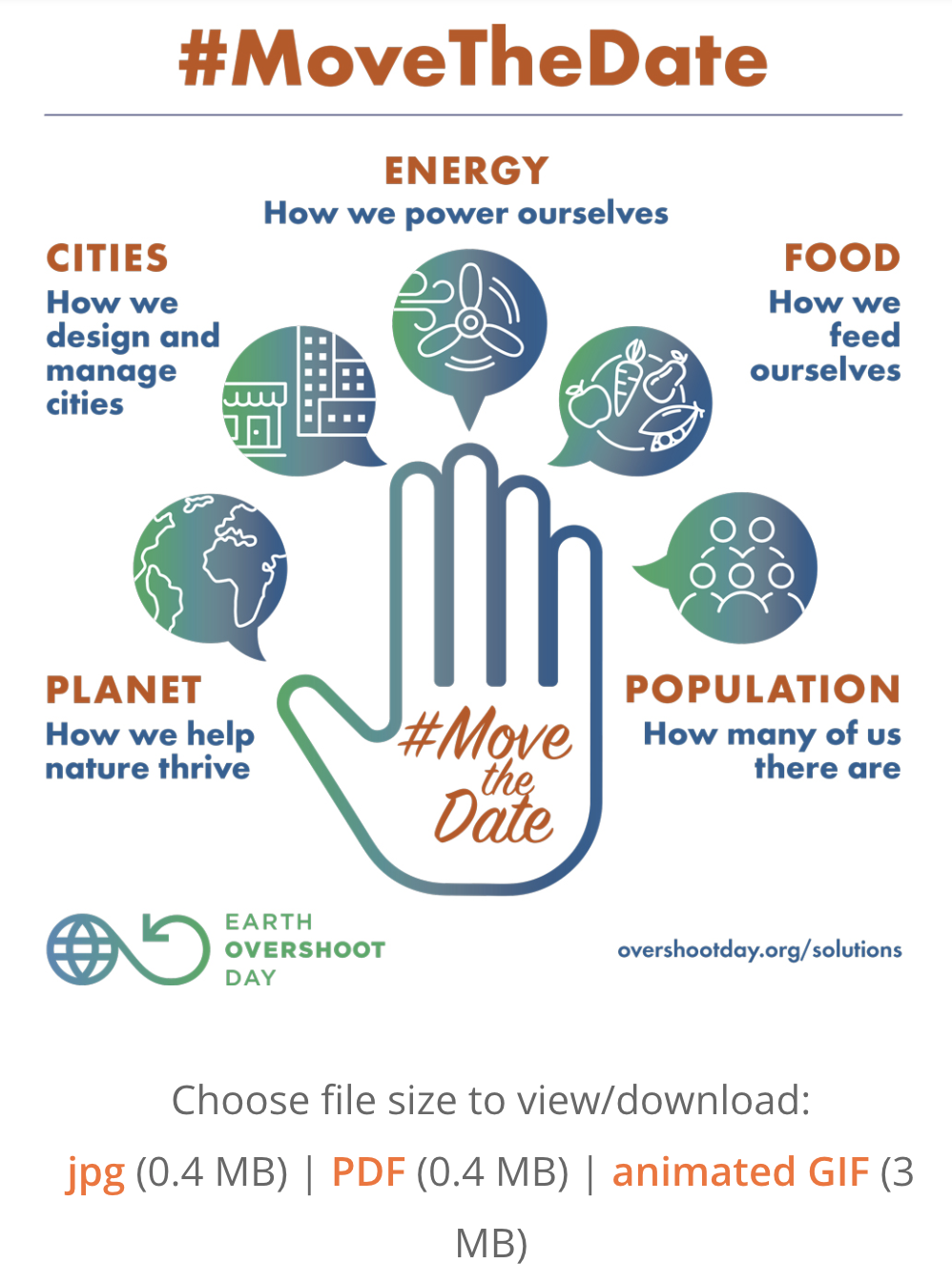

The solution to the polycrisis is not “green growth” or “sustainable development,” which are merely softer versions of the cult of omnicide. The solution is to shrink towards abundance. This concept, articulated in the Population Balance podcast, challenges the core tenet of modern economics: that more is better. We must consider a new understanding of what we need more of.

Shrinking towards abundance is a paradox only to the indoctrinated mind. It means shrinking our material footprint, our energy consumption, and our population (through the empowerment of women and the rejection of pronatalism), in order to increase the abundance of:

Time: Freedom from the 40+ hour workweek and the labor arbitrage machine.

Connection: Deep relationships with community and kin.

Nature: An “abundance agenda for nature” that prioritizes the restoration of wildlife, the return of keystone species like beavers and salmon, and the protection of migration corridors like the Yellowstone-to-Yukon. We must not destroy the forests we have left, the habitats that are relatively untouched. We must leave Great Nature with its freely evolving living systems alone to regenerate biological abundance.

Meaning: The satisfaction of living in alignment with the “Great Mystery.”

Cosmopolitan Localism and Tech-for-Gaia

We must use technology to develop fair and sustainable trading networks that ‘price in’ the value of living systems. A culture that is in a deep, intimate relationship with living systems aligns with the model of Cosmopolitan Localism.

Localize Atoms: We must shrink our physical economies to fit local and regional constraints. Food, energy, and goods should be produced as locally as possible, while respecting the bioregion's limits to growth.

Globalized Aspects: We should use technology to support scientific, technical, and engineering collaboration across cultures. The internet should be used not for AI-generated distraction but for the sharing of knowledge on ecological restoration, regenerative agriculture, and appropriate technology.

Pricing in Life: Trading networks must internalize the cost of ecological destruction. A product that destroys a forest must be prohibitively expensive, or, in some cases, not permitted on pain of death, reflecting its true cost to the biosphere.

The Movement of Young Leaders

It is practically impossible to convince people trained and educated in these pernicious economic belief systems to change their minds. The older generations are too invested in the Ponzi scheme of modern industrial civilization. Therefore, a deeply committed group of young leaders will have to lead a revolutionary movement that disenfranchises our present power brokers, the pathological community of what I call Players of the Great Game 21st Century.

The Players know not what they do, and they need not be forgiven.

Our new leaders must be immune to the digital distractions that keep their peers docile. They must look to the “Guardians of the Earth”—Cooper, Eastman, Silko, Vizenor—for their values. They must understand that the failure of neoliberal globalism is an opportunity to build something new—something that is not genocidal, ecocidal, and disruptive to healthy, stable cultures. They must practice survivance: an active, creative, and joyous resistance to the cult of death.

To practice survivance is to actively assert a presence, resilience, and cultural continuity rather than defining oneself simply as a victim of historical trauma or a passive survivor of colonial genocide. Coined by Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor, the term combines survival and resistance, emphasizing a renunciation of dominance, tragedy, and victimry through creative and active means.

Aspects of practicing survivance include:

Active Presence over Victimry: Survivance moves beyond merely living through traumatic events (“survival”) to actively create a presence in the world. It rejects narratives that portray Indigenous peoples only as broken or vanishing. (One could think of Palestinians.)

Cultural Continuance and Creativity: It involves the perpetuation of stories, traditions, and culture, often employing humor, irony, and storytelling to resist, rather than merely react to, colonial pressures.

Decolonization in Daily Life: It is a daily practice, not merely a historical event, that can include reclaiming language, practicing traditional arts, maintaining sovereignty, and engaging in community building.

Examples of Acts:

Storytelling/Art: Creating art that tells a story of active, modern existence.

Digital Media: Using video games to share Indigenous stories and perspectives.

Cultural Practices: Engaging in traditional dances or ceremonies, such as the Palestinian dabke, to assert identity and joy against occupation.

Language: Revitalizing and using Indigenous languages, as they contain “boundless potential of discovery.”

Survivance serves as an “active sense of presence” that helps individuals and communities reframe their experiences, focusing on strength, joy, and endurance.

A Vision of the Pristine

We must not let our individual comfort and prosperity prevent us from understanding and prioritizing biophysical reality and the limits to growth. Pain, suffering, and death may come for all of us soon as the inevitable result of 5,000 years of progress narratives that encourage war with ourselves, each other, and against Gaia. But collapse is also a clearing.

Imagine, for a moment, what it might be like to live in a new world we could create, simply by slowing down and listening to Great Nature.

Imagine a society that has “shrunk” back into the embrace of the Earth. You wake in a community that is egalitarian by design, where the “freedom to disobey” ensures that no tyrant can hoard power. The air is pristine, the water is clear, and the landscape is a mosaic of “tame” abundance—gardens, forests, and herds, managed with the wisdom of the Wendat and the Lakota.

There is no labor arbitrage here; you work for your community, and your work has visible meaning and impact. You are not a colonial subject or a “consumer,” but a citizen of a specific watershed. The “hard problem” of consciousness has dissolved because you are never alone; you are in constant, silent dialogue with the living world. You feel the “mothering power” of the soil that Standing Eagle spoke of. You know the “blessedness of enough” that Seton described.

Technological networks connect you to the global mind, not to sell you ads, but to share the joy of discovery and the beautiful variety of culture. You hear a report from the other side of the world about the recovery of a coral reef, and you feel it as a personal victory.

GAIA is a miracle. She has waited patiently for us to wake up from our fever dream of conquest. The real hard problem is solved the moment we stop trying to reinvent the world and start trying to love it. We are not the masters of this planet; we are its children. And it is time to come home.

This is not our future, although it is an enjoyable movie with some moral lessons embedded in its story.

I share this with you today because my perspective is rooted in a lifelong vision: a dream of old-growth forests and the resilient, grounded communities that once thrived within them. For decades, I have carried this image of a more natural world—making it all the more gut-wrenching to reconcile that dream with a global reality defined by systemic injustice, violence, and ecological destruction.

We must challenge the complacency found from Toledo to Tokyo, and Sydney to Paris. This ‘thing of ours’ is not inevitable, nor is it the best of all possible worlds. While our current human ecological density makes a return to the forest difficult, we must recognize that the status quo is a choice we continue to make every day.

The insulation of affluence is thinning. Soon, the gathering forces of the polycrisis will make these impacts impossible to ignore, even for those currently shielded by wealth. We are approaching a definitive threshold where the survivors of this madness will be forced to face the same crossroads that led us here. We cannot afford to hand them the same broken cultural map. For those who understand the gravity of this moment, the time for observation is over. It is time to get busy.