Humans Evolved Into A Kill Switch

The story of our brain’s evolution is complex, an inquiry of which would require a more than cursory understanding of multiple domains of science. It’s a fascinating story, and I recommend you look into it while the lights are still on. Our unique evolved anatomy produced “culture,” a Killer App, which is probably the most complex thing one can think of.

It’s a fascinating story, and I recommend you look into it while the lights are still on. Our unique evolved anatomy produced “culture,” a Killer App, which is probably the most complex thing one can think of.

Recently, I’ve been immersing myself in history books and podcasts, driven by a deep curiosity about how we, as a species, have lived, fought, and died throughout our history. When I say history, I’m not referring to the entire timeline of the past, which is studied through various disciplines like paleontology, archaeology, cosmology, physics, biology, geology, and genealogy.

Human history began when Homo sapiens sapiens (modern humans) first appeared, currently estimated to be around 300,000 years ago in Africa.

At present, I am more interested in history after the invention of writing, as opposed to pre-his-story.

If we take the invention of writing as the marker, Sumerian cuneiform script in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), with the earliest evidence dating back to around 3400–3200 BCE, and Egyptian hieroglyphs, with the earliest known examples also dating to around 3200 BCE. History began around the late 4th millennium BCE (around 3200 BCE) in regions like Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Search Break: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Mathematics and Rationalism are Killer Apps.

Global cultural history is a lot harder to get a glimpse of, as there is not much evidence about many cultures. Oral traditions are mostly broken, fragmented, and complicated by interactions with other traditions. Some may still exist, but they are few and can’t be traced back to thousands and thousands of years. I am not familiar with debates on the topic, but you know what I mean.

Search Break: Pythagoras.

From this perspective, the vast majority of human existence falls under pre-his-story.

From my exploration of history and prehistory, I have noticed specific innovations I think of as “killer apps” — human innovations that, while initially felt to be beneficial, ultimately contain the seeds of our destruction.

Many thinkers have and are examining the unintended consequences of technological advancement and the role of cultural narratives in driving unsustainable practices and ways of life.

My interests are nothing new. Below are a few killer apps that have emerged along the timeline of our cultural evolution. I’m guessing complex spoken language was one of the first killer apps. Followed by:

Early Toolmaking: Facilitating migration, hunting, and basic survival.

Agriculture and Settlement: Enabling larger populations and the storage of resources.

Trade Networks: Fostering interconnectedness and resource exchange.

Ships and Navigation: Leading to exploration, trade, and ultimately colonialism/imperialism and a fossil-fueled modern techno-industrial global economy, and Ubiquitous Human Techno-Waste.

Metallurgy (Bronze/Iron Age): Revolutionizing tools, agriculture, and warfare.

Logic and mathematics.

Fossil Fuels and the Steam Engine: Powering the Industrial Revolution and Unprecedented Resource Exploitation.

Communication Technologies (Telegraph, etc.): Enabling global information networks, scientific collaboration, and managing complex systems.

Advanced Weaponry (Industrial Age to Nuclear, etc.): Increasing the scale and destructive global conflicts and wars, and inevitably the automated destruction of everything on Earth. I know, that’s a bold statement, but if you can do the math, you will understand.

Global Trade and Finance: Creating intricate interconnectedness, systemic vulnerabilities, and inequalities. Borrowing energy and materials from future generations, with no way of paying them back when we are gone. We live in a world of limited resources and seemingly unlimited constructs, conventions, and narratives. But really, it’s all Shakespeare. Right?

All of the above are increasing in complexity as scientific, engineering, and technological innovations create second and third-order problems to fix, as the overall complexities of interconnected energy and material extraction and flows make systems more fragile, and competition for control of these systems more contentious and potentially destructive to the systems themselves and the people who maintain them.

We earn currency from markets that track the problems we create and solve for profit. We market solutions that create more problems. If you are in the right circumstances in this Great Game, you can have a fantastically wealthy experience with an intoxicating illusion of control.

More people experience this illusion of control and wildly wealthy lives than ever before. There are more wealthy people per capita on Earth than at any time in history, and more poor and miserable people as well. That’s merely a numbers game, and numbers can be played with to justify many disparate narratives and the goals that underpin them.

The development and deployment of these “Killer Apps” have been consistently justified by cultural narratives, such as philosophy, mythology, mystery traditions, The Gods, Big Gods, religion, divine right, jingoism, imperialism, racism, and nationalism. These stories and ideas have fueled expansionism, conflict, and the relentless pursuit of growth: stories, stories, and more stories with their justifying narratives, ideologies, and belief systems are at the very heart of the logic of the Great Game.

This trajectory, despite the initial benefits of these innovations for human groups, is leading towards:

Genocide: Fueled by ideologies of supremacy and othering.

Ecocide: Resulting from unsustainable resource extraction, environmental degradation, and habits of life.

Overshoot: Exceeding the Earth’s carrying capacity for complex evolving living systems that we are part and parcel of and depend on for our existence. Life begets Life. Life depends on Life. However, we define Life at any particular time, as far as we know, this is the only living system (GAIA) in the Universe.

Global Civilizational Collapse: The potential outcome of unchecked ecological destruction, societal instability, and various psychological and physiological pathologies emerging from false beliefs, a maladaptive misunderstanding of Great Nature, and destructive ways of life that ignore how we can sustainably exist within Great Nature’s rules/limits.

Extinction: The ultimate consequence of a fundamentally unsustainable path.

My website has dozens of URLs and book recommendations covering killer apps that have emerged throughout history. Good information is at our fingertips, but we hardly care to delve into it as we struggle to survive or gain prestige.

All of these authors, individuals, and groups must be understood within their context and not be thought of as disseminating “The Truth.” Despite the inadequacies of our shallow wisdom and understanding of the Universe and our place in it, I enjoy exploring different ways of understanding aspects of “Reality,” which is ultimately too complex and vast for any individual, community, or human network to grasp.

All narratives are disputed and change over time as new information and methods of inquiry are discovered, and as stories are edited and rewritten for a desired effect. Although powerful lines of evidence support some of these narratives, they don’t represent, in general, a total understanding of complex, evolving, and emergent systems of Great Living Nature.

Panpsychism. Life. Consciousness. Dark energy. Dark matter. What is it, and how does it all work? Can we extract minerals and energy from the ocean floor at a reasonable cost, plus profits to maintain the acceleration of The Great Game 2.0? Do we have the time, resources, and energy to mine asteroids or terraform Mars? Can I upload my sense of body, mind, and soul, my memories, identity, and ego to a chip on a computer and live happily forever after? Will I get to stay in my body for a thousand years, or can I go to heaven in my spirit form and enjoy whatever people do there? Are bad, stupid people trying to stop me from creating an intentional community of people in Ireland with pure, genetically verified Celtic folks? If these bad folks want to stop me from my Celtic dream, what can I do about it? What does God want? What happens to us when we die? Does God want us to rebuild the Temple? Do U.S. Americans have to control AI because if the Chinese did, the world would be FUBAR? Is the American Pope a good guy?

We will never know it all, and neither will our machines.

We exist and do what we do based on the compelling Nature of our stories and how that forms our identity within our group of true believers. We are no longer intimately connected to Great Nature, so our primary concerns revolve around the Great Game of competition for dominance between large-scale groups. We are addicted to stories and compelled to act them out as best we can.

Why didn’t they write E=mc² on one of the tablets Moses brought down from the mountain? Why were the Israelites dancing around a golden calf?

I will leave my thoughts on transcendent, supernatural things to my private musings, creative writing, and intimate conversations with trusted and loved friends. A productive or whimsical imagination is nice to have.

None of the few books on my book recommendation page at Cospolon are “the best books” on a particular subject or narrative line of inquiry or explanation. The webpage hardly represents a complete library, and many books I have encountered are left out. Still, they are, I think, informative and helpful in understanding our current Great Singular Polycrisis that has emerged from our “Nature.” Read some of them if you will. It won’t make you holy, rich, powerful, or a “useful intellectual,” but it might help you prepare your heart and mind for the collapse of Complex Global Civilization.

I am at a loss thinking whether I should rewrite my manifesto page or simply delete it. Manifestos are illusions developed by delusions as a virtue crutch in the face of absurd circumstances that are only useful if they have a practical application that can be measured in the medium term.

No one knows what Medieval Period 2.0 will be like, but these days I like imagining it and writing about it. If I am going to write fiction, that’s the direction for me. Manifestos? Didn’t the Great War, the dot-com/housing crisis/whatnot crash happen decades ago, and every decade since? Have dreamers and protopians not been continually disappointed?

“Our team never won, but it’s my home team and I love it and root for it every season.”

If you take breaks from the emotional roller coaster constantly imposed on the brain/body’s endocrine system with its neurotransmitters and hormones, by supernormal stimuli from the hyperobjects of modern ideas, conveniences, and entertainments, you surely must be a little disappointed by the rhymes of modern life.

Much has been written about such things.

If you look into it, you will discover that modern techno-industrial civilization flipped the kill switch long ago. What looks like progress is actually the ongoing collapse of global civilization on an unprecedented scale, and the collapse is speeding up and hitting tipping points. Those living during the epic tale’s end will experience more pain, horror, and violence than any Empire’s collapse in the history of civilization.

Soon it will feel like “The Long Excruciating Tooth Ache.”

I wish my puny knowledge and intuitions didn’t arrive at such conclusions.

I want to frolic and sing as I forest bathe and drink from pristine rivers in the wilderness with animals coming to serve, feed, and keep me company as I wonder at the beauty of it all. I want to spend the afternoon singing extemporaneous poetry for the dragonflies.

In the coming years, we will mourn the loss of many conveniences. Selfishly, this idiotic storytelling baby boomer hopes I can keep my relatively easy life going as I grow older and approach my inevitable end.

I imagine I can take the pain and accept my death with dignity, courage, and with love in my heart.

Believing any group or individual has all or even some of the answers is a perilous attitude. But we don’t call it “Hopium” for nothing. All we can do is try our best to understand and prepare for the cascading predicaments we find ourselves in.

Search Break: The Buddhist Canon (Tripitaka).

Search Break: The Gospel According to Thomas.

The illusion is falling apart as we desperately cling to magic.

But inquiry can also lead to our understanding of what’s truly important and valuable. Some of us may find intimacy again.

WEIRD, Anglo supremacists have had a successful run, depending on how you define success.

I can only testify to my good fortune and what that means to me.

The world has learned from the Western way and adopted it. I have included an epic poem below that I hope you will read, absorb, and think about.

The idea of pursuing knowledge or experience fully or not at all exists across cultures. We are often advised to dedicate ourselves to a course of action, such as learning or exploration, in a thorough way, rather than just superficially dipping into it. Today, we need to dedicate ourselves to a thorough understanding of how Great Nature works and find our proper place within its living systems.

Unfortunately, we are not interested in what Nature has to teach us, so now, the final and greatest acceleration has begun.

The “Great Acceleration” typically refers to the period after World War II, specifically from the mid-20th century onwards, with its unprecedented global surge of activities and their impacts on GAIA (complex living systems).

The concept of the Great Acceleration is supported by numerous scientific studies that began around 1950. Good examples of this kind of work can be found at the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) and the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

The Great Acceleration is a term used to describe the rapid and widespread increase in human activity and its impact on Earth’s natural systems, which began around the mid-20th century. It is often associated with the Anthropocene epoch, a proposed geological era marked by significant human influence on the Earth’s ecosystems and climate. The Great Acceleration encompasses various social, economic, and environmental changes that have occurred on a global scale since the 1950s.

During the Great Acceleration, remarkable socioeconomic and Earth system trends have been observed. Global population has surged from approximately 2.5 billion in 1950 to nearly 8 billion by 2021, and the urban population has increased from 29% in 1950 to around 56% in 2021. The world GDP has grown from $9 trillion in 1950 to over $84 trillion in 2021 (in constant 2011 US dollars). Alongside these trends, earth system changes have accelerated, with atmospheric CO2 concentrations rising from 310 ppm in 1950 to over 410 ppm by 2021. The global average temperature has increased by approximately 1.2°C since the pre-industrial era, and the rate of species extinction is estimated to be 100–1,000 times higher than the background rate. Furthermore, plastic production has skyrocketed from 2 million metric tons in 1950 to over 360 million metric tons in 2021, and the global use of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilisers has risen dramatically, contributing to water pollution and eutrophication.

Our narratives and tools produced exponential increases in socioeconomic trends and ideologies (like neoliberalism). Modernity is destroying Earth's ecosystems. We read every day about the sixth extinction caused by agriculture, ocean acidification, deforestation, CO2 emissions, and so on. These interconnected trends illustrate how human activity has become the dominant driver of planetary change, leading to the proposed and debated Anthropocene epoch.

Rapidly evolving narratives and technologies in the basket we call Artificial Intelligence represent warp-speed acceleration compared to the recklessness of our last great acceleration.

But this is not the first era of acceleration. Others include the Neolithic revolution (c. 10,000 BCE onwards), the rise of early civilizations and urbanization (c. 4th-1st millennium BCE), the Age of Exploration and Colonization (c. 15th-18th centuries CE), and the Industrial Revolution (c. 18th-19th centuries CE). Of course, this is not a definitive breakdown or a complete list.

The Techno-Industrial AI, Robotic, Anthropocene is the Potential “Final” Great Acceleration, the ultimate “Kill Switch.”

The current acceleration is unique in its global scale, with its speed of technological change, black box nature, and the magnitude of its impact on Earth’s systems. And most people are oblivious to it, believing only the reality they’ve been conditioned and trained to believe.

Artificial intelligence has the potential to dramatically accelerate technological development and resource exploitation, potentially outpacing our ability to understand and manage its consequences or control its trajectory.

The Maximum Power Principle, Jevons Paradox, and other models of our limited understanding of how nature and society work are constantly at play here.

Even those trying to keep up can’t.

Search Break: Thermodynamics.

The increasing global population, consumption rates, and resource scarcity exacerbated by environmental degradation will intensify conflicts and destabilize whatever global order we think we have at present. BRICS, the U.S.’s “Rules-Based Order,” or whatever, has no strategy to confront “overshoot” or even the desire to contemplate limits to growth.

To the contrary, it’s a mad fight to preserve business as usual even if it kills us.

For now, in the so-called first world, we are too well fed and entertained to care. We will continue to take from the rest of the world to satisfy our appetites. The true cost of our lifestyle is out of sight and out of mind; it’s truly incomprehensible for most of us.

The combination of environmental destruction (ecocide), the potential for large-scale conflict (see the war in Ukraine and the genocide in Gaza with its rapid innovations in drone and robotic weaponry, targeting technologies, enabled by complex communications systems like Starlink, and remote identification of targets and kill chain operations), along with the risks associated with uncontrolled advanced technologies like AI present unprecedented existential risks to humanity. All of this has already been causing species extinction and polluting our world for a long time.

We have been consuming everything we can for thousands of years and have not learned to listen to wise people simply asking us to slow down and pay more attention to Great Nature.

“Killer Apps” have always been killers. Technological power and cultural narratives decoupled from an intimate understanding of the complexities of living systems create a dangerous feedback loop. The narratives of progress, supremacy, and endless growth blind us to the long-term consequences of our innovations and ways of life.

Narratives of human dominance over Nature and the right to exploit resources for economic gain have historically driven environmental destruction for tens of thousands of years.

Ideologies of nationalism, imperialism, and racial superiority have justified wars and genocides, amplified by increasingly powerful weaponry (“War Is The Thing That Gives Life Meaning,” a “Killer App”).

Entrenched cultural values and economic systems prevent us from adopting sustainable practices and the necessary paradigm shifts to avert ecological collapse.

Our ingenuity and capacity for manipulating Nature have led to unprecedented population growth and technological advancement. However, this very success, driven by “Killer Apps” and the narratives that propel them, is now threatening the planet’s living systems upon which we owe long-term survival.

How many more ways can all of us who are tuned into this say it?

At some point, we will all tire of sounding the alarm and sit back to wait for the silent spring.

The historical development of increasingly potent tools, coupled with cultural narratives that often prioritize short-term gains and intergroup competition, has created a situation where our successes drive us toward environmental destruction and potential extinction. The academic and scientific literature across various disciplines increasingly supports the idea that unchecked technological advancement within unsustainable cultural frameworks poses a significant threat to the future of our species and Life on Earth.

Addressing this challenge requires a fundamental shift in our cultural narratives and a conscious effort to develop and deploy technologies in a way that respects ecological limits and promotes long-term sustainability.

Can this be done? Can we preserve the good stuff and get rid of the bad stuff?

I must laugh.

It would take a miracle. Do you believe in miracles?

Our history and its narratives warp our understanding of our place in Nature. Circumstances and predicaments are brutal dictators that will determine what we do next, and after that, and on and on until we can’t fix what we’ve broken out of a sheer instinct to survive.

Can destroyers ever truly be creators?

Search Break: Look into the sizes and populations of villages worldwide at specific times and places. Start in Ancient Egypt and move forward in time, continuing your round-the-world journey. It’s an enlightening exercise.

Science, engineering, and technology create amazing things and complex problems that can only be fixed with more science, engineering, and technology.

Our machines will turn the Universe into Hammers and Nails.

Neoreactionary, TESCREAL accelerationism works toward replacing life with an artificial machine that will somehow align with “human values.” What kind of human values? The values of Tech Bros with delusions of being Gods? A machine, by its definition, can never align with human values because humans are just another animal embedded in Great Nature with all its limits, quirks, and ever-evolving potential. When the machine iterates its algorithms, what will be its purpose? Despite our inventions and predictions, we may never know.

What do you value?

The problem of evil is trivial next to the problem of the malfunctioning Nature of our great narratives that have produced the insatiable apex techno-industrial predator we have become.

Transforming a large-scale modern techno-industrial global culture may be impossible as we accelerate toward ultimate collapse.

Will the machine boot up just before the last creature dies?

What will be God’s next project?

Sin first, heat death later.

Do we really think we know?

We will concern ourselves with pop stars, season tickets to the game, and fighting over what story is supreme and sanctioned by God Almighty, or some heroic leader or thinker, giving us the right to do as we must.

What choices do you have?

Read and make history; do what you must; we are here now. I hope you are enjoying life. I am a modern techno-industrial narrator who has had a good run. If I were slightly more ignorant, I’d probably feel better than I do now. Or more stressed about achieving this and that, owning more stuff, and comparing better when measured against my competitors. I’ll never know the parallel universe selves. I live where I live not because it’s the perfect place. After a lifetime of travel and relocations, I thought this might be a slightly kinder, gentler place to watch global civilization unravel. Sadly, it’s falling apart faster than even a realist (haha, hehe) like me expected. I have friends in their 60s with young children; I can only say I hope they love and enjoy them. I can’t imagine what life will be like for them when they are 40.

I have been looking at what life was like in the past when there were far fewer people on Earth. For most of our “History,” life has been tough for most folks and violent for those wanting more or needing to migrate. Our history is marked by hard labor, conquest, brutal competition, oppression, subjugation, slavish service, and war. Read about ancient Mesopotamian kingdoms, ancient empires, and conquering hordes. Read about the Great Northern War, from 1700 to 1721, involving Tsar Peter the Great of Russia against the Swedish Empire, led by King Charles XII.

Have mercy!

If you weren’t part of the elite, life was hard. But even elites lived risky, dangerous lives, mostly short and violent, with some pageantry, feasts, and romance here and there.

Surely there have been many moments of bliss.

The horrors of he past are unimaginable. Reading about them is challenging. We romanticize the past or hardly imagine it. The future will be like today, only better.

If we are reborn again and again, as in Vedic and Buddhist stories, I can understand why people want to be free from rebirth. You were not always a princess living with Prince Charming in a lovely castle by a lake. In the same vein, I can understand why people pine for God's love, forgiveness, and peace in heaven. Imagining Valhalla must have been of great comfort before a battle.

Modern techno-industrial global fossil-fueled civilization has been splendid to me. I wish we could keep it going and make it gentle, modest, and sustainable, but that is an impossible dream. We are selfish, arrogant consumers led by Players of The Great Game 2.0 who are all marked by dark tetrad characteristics and defend consumerism, competition, markets, and the seven deadly sins for fear of losing their careers, their privileged place in society, respect, power, and control.

“I just want to fit in!” Patrick Bateman.

We are insane. We no longer fit into Great Nature. We have banished our souls to the wilderness of dark dreams.

Oh, what a wonder to dream an impossible dream. Would I were able to make it up as I go along.

An Essay on Criticism

PART 1

’Tis hard to say, if greater want of skill

Appear in writing or in judging ill;

But, of the two, less dang’rous is th’ offence

To tire our patience, than mislead our sense.

Some few in that, but numbers err in this,

Ten censure wrong for one who writes amiss;

A fool might once himself alone expose,

Now one in verse makes many more in prose.

’Tis with our judgments as our watches, none

Go just alike, yet each believes his own.

In poets as true genius is but rare,

True taste as seldom is the critic’s share;

Both must alike from Heav’n derive their light,

These born to judge, as well as those to write.

Let such teach others who themselves excel,

And censure freely who have written well.

Authors are partial to their wit, ’tis true,

But are not critics to their judgment too?

Yet if we look more closely we shall find

Most have the seeds of judgment in their mind;

Nature affords at least a glimm’ring light;

The lines, tho’ touch’d but faintly, are drawn right.

But as the slightest sketch, if justly trac’d,

Is by ill colouring but the more disgrac’d,

So by false learning is good sense defac’d;

Some are bewilder’d in the maze of schools,

And some made coxcombs Nature meant but fools.

In search of wit these lose their common sense,

And then turn critics in their own defence:

Each burns alike, who can, or cannot write,

Or with a rival’s, or an eunuch’s spite.

All fools have still an itching to deride,

And fain would be upon the laughing side.

If Mævius scribble in Apollo’s spite,

There are, who judge still worse than he can write.

Some have at first for wits, then poets pass’d,

Turn’d critics next, and prov’d plain fools at last;

Some neither can for wits nor critics pass,

As heavy mules are neither horse nor ass.

Those half-learn’d witlings, num’rous in our isle

As half-form’d insects on the banks of Nile;

Unfinish’d things, one knows not what to call,

Their generation’s so equivocal:

To tell ’em, would a hundred tongues require,

Or one vain wit’s, that might a hundred tire.

But you who seek to give and merit fame,

And justly bear a critic’s noble name,

Be sure your self and your own reach to know,

How far your genius, taste, and learning go;

Launch not beyond your depth, but be discreet,

And mark that point where sense and dulness meet.

Nature to all things fix’d the limits fit,

And wisely curb’d proud man’s pretending wit:

As on the land while here the ocean gains,

In other parts it leaves wide sandy plains;

Thus in the soul while memory prevails,

The solid pow’r of understanding fails;

Where beams of warm imagination play,

The memory’s soft figures melt away.

One science only will one genius fit;

So vast is art, so narrow human wit:

Not only bounded to peculiar arts,

But oft in those, confin’d to single parts.

Like kings we lose the conquests gain’d before,

By vain ambition still to make them more;

Each might his sev’ral province well command,

Would all but stoop to what they understand.

First follow NATURE, and your judgment frame

By her just standard, which is still the same:

Unerring Nature, still divinely bright,

One clear, unchang’d, and universal light,

Life, force, and beauty, must to all impart,

At once the source, and end, and test of art.

Art from that fund each just supply provides,

Works without show, and without pomp presides:

In some fair body thus th’ informing soul

With spirits feeds, with vigour fills the whole,

Each motion guides, and ev’ry nerve sustains;

Itself unseen, but in th’ effects, remains.

Some, to whom Heav’n in wit has been profuse,

Want as much more, to turn it to its use;

For wit and judgment often are at strife,

Though meant each other’s aid, like man and wife.

’Tis more to guide, than spur the Muse’s steed;

Restrain his fury, than provoke his speed;

The winged courser, like a gen’rous horse,

Shows most true mettle when you check his course.

Those RULES of old discover’d, not devis’d,

Are Nature still, but Nature methodis’d;

Nature, like liberty, is but restrain’d

By the same laws which first herself ordain’d.

Hear how learn’d Greece her useful rules indites,

When to repress, and when indulge our flights:

High on Parnassus’ top her sons she show’d,

And pointed out those arduous paths they trod;

Held from afar, aloft, th’ immortal prize,

And urg’d the rest by equal steps to rise.

Just precepts thus from great examples giv’n,

She drew from them what they deriv’d from Heav’n.

The gen’rous critic fann’d the poet’s fire,

And taught the world with reason to admire.

Then criticism the Muse’s handmaid prov’d,

To dress her charms, and make her more belov’d;

But following wits from that intention stray’d;

Who could not win the mistress, woo’d the maid;

Against the poets their own arms they turn’d,

Sure to hate most the men from whom they learn’d.

So modern ‘pothecaries, taught the art

By doctor’s bills to play the doctor’s part,

Bold in the practice of mistaken rules,

Prescribe, apply, and call their masters fools.

Some on the leaves of ancient authors prey,

Nor time nor moths e’er spoil’d so much as they:

Some drily plain, without invention’s aid,

Write dull receipts how poems may be made:

These leave the sense, their learning to display,

And those explain the meaning quite away.

You then whose judgment the right course would steer,

Know well each ANCIENT’S proper character;

His fable, subject, scope in ev’ry page;

Religion, country, genius of his age:

Without all these at once before your eyes,

Cavil you may, but never criticise.

Be Homer’s works your study and delight,

Read them by day, and meditate by night;

Thence form your judgment, thence your maxims bring,

And trace the Muses upward to their spring;

Still with itself compar’d, his text peruse;

And let your comment be the Mantuan Muse.

When first young Maro in his boundless mind

A work t’ outlast immortal Rome design’d,

Perhaps he seem’d above the critic’s law,

And but from Nature’s fountains scorn’d to draw:

But when t’ examine ev’ry part he came,

Nature and Homer were, he found, the same.

Convinc’d, amaz’d, he checks the bold design,

And rules as strict his labour’d work confine,

As if the Stagirite o’erlook’d each line.

Learn hence for ancient rules a just esteem;

To copy nature is to copy them.

Some beauties yet, no precepts can declare,

For there’s a happiness as well as care.

Music resembles poetry, in each

Are nameless graces which no methods teach,

And which a master-hand alone can reach.

If, where the rules not far enough extend,

(Since rules were made but to promote their end)

Some lucky LICENCE answers to the full

Th’ intent propos’d, that licence is a rule.

Thus Pegasus, a nearer way to take,

May boldly deviate from the common track.

Great wits sometimes may gloriously offend,

And rise to faults true critics dare not mend;

From vulgar bounds with brave disorder part,

And snatch a grace beyond the reach of art,

Which, without passing through the judgment, gains

The heart, and all its end at once attains.

In prospects, thus, some objects please our eyes,

Which out of nature’s common order rise,

The shapeless rock, or hanging precipice.

But tho’ the ancients thus their rules invade,

(As kings dispense with laws themselves have made)

Moderns, beware! or if you must offend

Against the precept, ne’er transgress its end;

Let it be seldom, and compell’d by need,

And have, at least, their precedent to plead.

The critic else proceeds without remorse,

Seizes your fame, and puts his laws in force.

I know there are, to whose presumptuous thoughts

Those freer beauties, ev’n in them, seem faults.

Some figures monstrous and misshap’d appear,

Consider’d singly, or beheld too near,

Which, but proportion’d to their light, or place,

Due distance reconciles to form and grace.

A prudent chief not always must display

His pow’rs in equal ranks, and fair array,

But with th’ occasion and the place comply,

Conceal his force, nay seem sometimes to fly.

Those oft are stratagems which errors seem,

Nor is it Homer nods, but we that dream.

Still green with bays each ancient altar stands,

Above the reach of sacrilegious hands,

Secure from flames, from envy’s fiercer rage,

Destructive war, and all-involving age.

See, from each clime the learn’d their incense bring!

Hear, in all tongues consenting pæans ring!

In praise so just let ev’ry voice be join’d,

And fill the gen’ral chorus of mankind!

Hail, bards triumphant! born in happier days;

Immortal heirs of universal praise!

Whose honours with increase of ages grow,

As streams roll down, enlarging as they flow!

Nations unborn your mighty names shall sound,

And worlds applaud that must not yet be found!

Oh may some spark of your celestial fire

The last, the meanest of your sons inspire,

(That on weak wings, from far, pursues your flights;

Glows while he reads, but trembles as he writes)

To teach vain wits a science little known,

T’ admire superior sense, and doubt their own!

Part 2

Of all the causes which conspire to blind

Man’s erring judgment, and misguide the mind,

What the weak head with strongest bias rules,

Is pride, the never-failing vice of fools.

Whatever Nature has in worth denied,

She gives in large recruits of needful pride;

For as in bodies, thus in souls, we find

What wants in blood and spirits, swell’d with wind;

Pride, where wit fails, steps in to our defence,

And fills up all the mighty void of sense!

If once right reason drives that cloud away,

Truth breaks upon us with resistless day;

Trust not yourself; but your defects to know,

Make use of ev’ry friend — and ev’ry foe.

A little learning is a dang’rous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fir’d at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

In fearless youth we tempt the heights of arts,

While from the bounded level of our mind,

Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

But more advanc’d, behold with strange surprise

New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

So pleas’d at first, the tow’ring Alps we try,

Mount o’er the vales, and seem to tread the sky;

Th’ eternal snows appear already past,

And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

But those attain’d, we tremble to survey

The growing labours of the lengthen’d way,

Th’ increasing prospect tires our wand’ring eyes,

Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

A perfect judge will read each work of wit

With the same spirit that its author writ,

Survey the whole, nor seek slight faults to find,

Where nature moves, and rapture warms the mind;

Nor lose, for that malignant dull delight,

The gen’rous pleasure to be charm’d with wit.

But in such lays as neither ebb, nor flow,

Correctly cold, and regularly low,

That shunning faults, one quiet tenour keep;

We cannot blame indeed — but we may sleep.

In wit, as nature, what affects our hearts

Is not th’ exactness of peculiar parts;

’Tis not a lip, or eye, we beauty call,

But the joint force and full result of all.

Thus when we view some well-proportion’d dome,

(The world’s just wonder, and ev’n thine, O Rome!’

No single parts unequally surprise;

All comes united to th’ admiring eyes;

No monstrous height, or breadth, or length appear;

The whole at once is bold, and regular.

Whoever thinks a faultless piece to see,

Thinks what ne’er was, nor is, nor e’er shall be.

In ev’ry work regard the writer’s end,

Since none can compass more than they intend;

And if the means be just, the conduct true,

Applause, in spite of trivial faults, is due.

As men of breeding, sometimes men of wit,

T’ avoid great errors, must the less commit:

Neglect the rules each verbal critic lays,

For not to know such trifles, is a praise.

Most critics, fond of some subservient art,

Still make the whole depend upon a part:

They talk of principles, but notions prize,

And all to one lov’d folly sacrifice.

Once on a time, La Mancha’s knight, they say,

A certain bard encount’ring on the way,

Discours’d in terms as just, with looks as sage,

As e’er could Dennis of the Grecian stage;

Concluding all were desp’rate sots and fools,

Who durst depart from Aristotle’s rules.

Our author, happy in a judge so nice,

Produc’d his play, and begg’d the knight’s advice,

Made him observe the subject and the plot,

The manners, passions, unities, what not?

All which, exact to rule, were brought about,

Were but a combat in the lists left out.

“What! leave the combat out?” exclaims the knight;

“Yes, or we must renounce the Stagirite.”

“Not so by Heav’n” (he answers in a rage)

“Knights, squires, and steeds, must enter on the stage.”

So vast a throng the stage can ne’er contain.

“Then build a new, or act it in a plain.”

Thus critics, of less judgment than caprice,

Curious not knowing, not exact but nice,

Form short ideas; and offend in arts

(As most in manners) by a love to parts.

Some to conceit alone their taste confine,

And glitt’ring thoughts struck out at ev’ry line;

Pleas’d with a work where nothing’s just or fit;

One glaring chaos and wild heap of wit.

Poets, like painters, thus, unskill’d to trace

The naked nature and the living grace,

With gold and jewels cover ev’ry part,

And hide with ornaments their want of art.

True wit is nature to advantage dress’d,

What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d,

Something, whose truth convinc’d at sight we find,

That gives us back the image of our mind.

As shades more sweetly recommend the light,

So modest plainness sets off sprightly wit.

For works may have more wit than does ’em good,

As bodies perish through excess of blood.

Others for language all their care express,

And value books, as women men, for dress:

Their praise is still — “the style is excellent”:

The sense, they humbly take upon content.

Words are like leaves; and where they most abound,

Much fruit of sense beneath is rarely found.

False eloquence, like the prismatic glass,

Its gaudy colours spreads on ev’ry place;

The face of Nature we no more survey,

All glares alike, without distinction gay:

But true expression, like th’ unchanging sun,

Clears, and improves whate’er it shines upon,

It gilds all objects, but it alters none.

Expression is the dress of thought, and still

Appears more decent, as more suitable;

A vile conceit in pompous words express’d,

Is like a clown in regal purple dress’d:

For diff’rent styles with diff’rent subjects sort,

As several garbs with country, town, and court.

Some by old words to fame have made pretence,

Ancients in phrase, mere moderns in their sense;

Such labour’d nothings, in so strange a style,

Amaze th’ unlearn’d, and make the learned smile.

Unlucky, as Fungoso in the play,

These sparks with awkward vanity display

What the fine gentleman wore yesterday!

And but so mimic ancient wits at best,

As apes our grandsires, in their doublets dress’d.

In words, as fashions, the same rule will hold;

Alike fantastic, if too new, or old;

Be not the first by whom the new are tried,

Not yet the last to lay the old aside.

But most by numbers judge a poet’s song;

And smooth or rough, with them is right or wrong:

In the bright Muse though thousand charms conspire,

Her voice is all these tuneful fools admire,

Who haunt Parnassus but to please their ear,

Not mend their minds; as some to church repair,

Not for the doctrine, but the music there.

These equal syllables alone require,

Tho’ oft the ear the open vowels tire,

While expletives their feeble aid do join,

And ten low words oft creep in one dull line,

While they ring round the same unvaried chimes,

With sure returns of still expected rhymes.

Where’er you find “the cooling western breeze”,

In the next line, it “whispers through the trees”:

If “crystal streams with pleasing murmurs creep”,

The reader’s threaten’d (not in vain) with “sleep”.

Then, at the last and only couplet fraught

With some unmeaning thing they call a thought,

A needless Alexandrine ends the song,

That, like a wounded snake, drags its slow length along.

Leave such to tune their own dull rhymes, and know

What’s roundly smooth, or languishingly slow;

And praise the easy vigour of a line,

Where Denham’s strength, and Waller’s sweetness join.

True ease in writing comes from art, not chance,

As those move easiest who have learn’d to dance.

’Tis not enough no harshness gives offence,

The sound must seem an echo to the sense.

Soft is the strain when Zephyr gently blows,

And the smooth stream in smoother numbers flows;

But when loud surges lash the sounding shore,

The hoarse, rough verse should like the torrent roar.

When Ajax strives some rock’s vast weight to throw,

The line too labours, and the words move slow;

Not so, when swift Camilla scours the plain,

Flies o’er th’ unbending corn, and skims along the main.

Hear how Timotheus’ varied lays surprise,

And bid alternate passions fall and rise!

While, at each change, the son of Libyan Jove

Now burns with glory, and then melts with love;

Now his fierce eyes with sparkling fury glow,

Now sighs steal out, and tears begin to flow:

Persians and Greeks like turns of nature found,

And the world’s victor stood subdu’d by sound!

The pow’r of music all our hearts allow,

And what Timotheus was, is Dryden now.

Avoid extremes; and shun the fault of such,

Who still are pleas’d too little or too much.

At ev’ry trifle scorn to take offence,

That always shows great pride, or little sense;

Those heads, as stomachs, are not sure the best,

Which nauseate all, and nothing can digest.

Yet let not each gay turn thy rapture move,

For fools admire, but men of sense approve;

As things seem large which we through mists descry,

Dulness is ever apt to magnify.

Some foreign writers, some our own despise;

The ancients only, or the moderns prize.

Thus wit, like faith, by each man is applied

To one small sect, and all are damn’d beside.

Meanly they seek the blessing to confine,

And force that sun but on a part to shine;

Which not alone the southern wit sublimes,

But ripens spirits in cold northern climes;

Which from the first has shone on ages past,

Enlights the present, and shall warm the last;

(Though each may feel increases and decays,

And see now clearer and now darker days.)

Regard not then if wit be old or new,

But blame the false, and value still the true.

Some ne’er advance a judgment of their own,

But catch the spreading notion of the town;

They reason and conclude by precedent,

And own stale nonsense which they ne’er invent.

Some judge of authors’ names, not works, and then

Nor praise nor blame the writings, but the men.

Of all this servile herd, the worst is he

That in proud dulness joins with quality,

A constant critic at the great man’s board,

To fetch and carry nonsense for my Lord.

What woeful stuff this madrigal would be,

In some starv’d hackney sonneteer, or me?

But let a Lord once own the happy lines,

How the wit brightens! how the style refines!

Before his sacred name flies every fault,

And each exalted stanza teems with thought!

The vulgar thus through imitation err;

As oft the learn’d by being singular;

So much they scorn the crowd, that if the throng

By chance go right, they purposely go wrong:

So Schismatics the plain believers quit,

And are but damn’d for having too much wit.

Some praise at morning what they blame at night;

But always think the last opinion right.

A Muse by these is like a mistress us’d,

This hour she’s idoliz’d, the next abus’d;

While their weak heads, like towns unfortified,

Twixt sense and nonsense daily change their side.

Ask them the cause; they’re wiser still, they say;

And still tomorrow’s wiser than today.

We think our fathers fools, so wise we grow;

Our wiser sons, no doubt, will think us so.

Once school divines this zealous isle o’erspread;

Who knew most Sentences, was deepest read;

Faith, Gospel, all, seem’d made to be disputed,

And none had sense enough to be confuted:

Scotists and Thomists, now, in peace remain,

Amidst their kindred cobwebs in Duck Lane.

If Faith itself has different dresses worn,

What wonder modes in wit should take their turn?

Oft, leaving what is natural and fit,

The current folly proves the ready wit;

And authors think their reputation safe

Which lives as long as fools are pleased to laugh.

Some valuing those of their own side or mind,

Still make themselves the measure of mankind;

Fondly we think we honour merit then,

When we but praise ourselves in other men.

Parties in wit attend on those of state,

And public faction doubles private hate.

Pride, Malice, Folly, against Dryden rose,

In various shapes of Parsons, Critics, Beaus;

But sense surviv’d, when merry jests were past;

For rising merit will buoy up at last.

Might he return, and bless once more our eyes,

New Blackmores and new Milbourns must arise;

Nay should great Homer lift his awful head,

Zoilus again would start up from the dead.

Envy will merit, as its shade, pursue,

But like a shadow, proves the substance true;

For envied wit, like Sol eclips’d, makes known

Th’ opposing body’s grossness, not its own.

When first that sun too powerful beams displays,

It draws up vapours which obscure its rays;

But ev’n those clouds at last adorn its way,

Reflect new glories, and augment the day.

Be thou the first true merit to befriend;

His praise is lost, who stays till all commend.

Short is the date, alas, of modern rhymes,

And ’tis but just to let ’em live betimes.

No longer now that golden age appears,

When patriarch wits surviv’d a thousand years:

Now length of Fame (our second life) is lost,

And bare threescore is all ev’n that can boast;

Our sons their fathers’ failing language see,

And such as Chaucer is, shall Dryden be.

So when the faithful pencil has design’d

Some bright idea of the master’s mind,

Where a new world leaps out at his command,

And ready Nature waits upon his hand;

When the ripe colours soften and unite,

And sweetly melt into just shade and light;

When mellowing years their full perfection give,

And each bold figure just begins to live,

The treacherous colours the fair art betray,

And all the bright creation fades away!

Unhappy wit, like most mistaken things,

Atones not for that envy which it brings.

In youth alone its empty praise we boast,

But soon the short-liv’d vanity is lost:

Like some fair flow’r the early spring supplies,

That gaily blooms, but ev’n in blooming dies.

What is this wit, which must our cares employ?

The owner’s wife, that other men enjoy;

Then most our trouble still when most admir’d,

And still the more we give, the more requir’d;

Whose fame with pains we guard, but lose with ease,

Sure some to vex, but never all to please;

’Tis what the vicious fear, the virtuous shun;

By fools ’tis hated, and by knaves undone!

If wit so much from ign’rance undergo,

Ah let not learning too commence its foe!

Of old, those met rewards who could excel,

And such were prais’d who but endeavour’d well:

Though triumphs were to gen’rals only due,

Crowns were reserv’d to grace the soldiers too.

Now, they who reach Parnassus’ lofty crown,

Employ their pains to spurn some others down;

And while self-love each jealous writer rules,

Contending wits become the sport of fools:

But still the worst with most regret commend,

For each ill author is as bad a friend.

To what base ends, and by what abject ways,

Are mortals urg’d through sacred lust of praise!

Ah ne’er so dire a thirst of glory boast,

Nor in the critic let the man be lost!

Good nature and good sense must ever join;

To err is human; to forgive, divine.

But if in noble minds some dregs remain,

Not yet purg’d off, of spleen and sour disdain,

Discharge that rage on more provoking crimes,

Nor fear a dearth in these flagitious times.

No pardon vile obscenity should find,

Though wit and art conspire to move your mind;

But dulness with obscenity must prove

As shameful sure as impotence in love.

In the fat age of pleasure, wealth, and ease,

Sprung the rank weed, and thriv’d with large increase:

When love was all an easy monarch’s care;

Seldom at council, never in a war:

Jilts ruled the state, and statesmen farces writ;

Nay wits had pensions, and young Lords had wit:

The fair sat panting at a courtier’s play,

And not a mask went unimprov’d away:

The modest fan was lifted up no more,

And virgins smil’d at what they blush’d before.

The following licence of a foreign reign

Did all the dregs of bold Socinus drain;

Then unbelieving priests reform’d the nation,

And taught more pleasant methods of salvation;

Where Heav’n’s free subjects might their rights dispute,

Lest God himself should seem too absolute:

Pulpits their sacred satire learned to spare,

And Vice admired to find a flatt’rer there!

Encourag’d thus, wit’s Titans brav’d the skies,

And the press groan’d with licenc’d blasphemies.

These monsters, critics! with your darts engage,

Here point your thunder, and exhaust your rage!

Yet shun their fault, who, scandalously nice,

Will needs mistake an author into vice;

All seems infected that th’ infected spy,

As all looks yellow to the jaundic’d eye.

Part 3

Learn then what morals critics ought to show,

For ’tis but half a judge’s task, to know.

’Tis not enough, taste, judgment, learning, join;

In all you speak, let truth and candour shine:

That not alone what to your sense is due,

All may allow; but seek your friendship too.

Be silent always when you doubt your sense;

And speak, though sure, with seeming diffidence:

Some positive, persisting fops we know,

Who, if once wrong, will needs be always so;

But you, with pleasure own your errors past,

And make each day a critic on the last.

’Tis not enough, your counsel still be true;

Blunt truths more mischief than nice falsehoods do;

Men must be taught as if you taught them not;

And things unknown proposed as things forgot.

Without good breeding, truth is disapprov’d;

That only makes superior sense belov’d.

Be niggards of advice on no pretence;

For the worst avarice is that of sense.

With mean complacence ne’er betray your trust,

Nor be so civil as to prove unjust.

Fear not the anger of the wise to raise;

Those best can bear reproof, who merit praise.

‘Twere well might critics still this freedom take,

But Appius reddens at each word you speak,

And stares, Tremendous ! with a threatening eye,

Like some fierce tyrant in old tapestry!

Fear most to tax an honourable fool,

Whose right it is, uncensur’d, to be dull;

Such, without wit, are poets when they please,

As without learning they can take degrees.

Leave dangerous truths to unsuccessful satires,

And flattery to fulsome dedicators,

Whom, when they praise, the world believes no more,

Than when they promise to give scribbling o’er.

’Tis best sometimes your censure to restrain,

And charitably let the dull be vain:

Your silence there is better than your spite,

For who can rail so long as they can write?

Still humming on, their drowsy course they keep,

And lash’d so long, like tops, are lash’d asleep.

False steps but help them to renew the race,

As after stumbling, jades will mend their pace.

What crowds of these, impenitently bold,

In sounds and jingling syllables grown old,

Still run on poets, in a raging vein,

Even to the dregs and squeezings of the brain,

Strain out the last, dull droppings of their sense,

And rhyme with all the rage of impotence!

Such shameless bards we have; and yet ’tis true,

There are as mad, abandon’d critics too.

The bookful blockhead, ignorantly read,

With loads of learned lumber in his head,

With his own tongue still edifies his ears,

And always list’ning to himself appears.

All books he reads, and all he reads assails,

From Dryden’s Fables down to Durfey’s Tales.

With him, most authors steal their works, or buy;

Garth did not write his own Dispensary .

Name a new play, and he’s the poet’s friend,

Nay show’d his faults — but when would poets mend?

No place so sacred from such fops is barr’d,

Nor is Paul’s church more safe than Paul’s churchyard:

Nay, fly to altars; there they’ll talk you dead:

For fools rush in where angels fear to tread.

Distrustful sense with modest caution speaks;

It still looks home, and short excursions makes;

But rattling nonsense in full volleys breaks;

And never shock’d, and never turn’d aside,

Bursts out, resistless, with a thund’ring tide.

But where’s the man, who counsel can bestow,

Still pleas’d to teach, and yet not proud to know?

Unbias’d, or by favour or by spite;

Not dully prepossess’d, nor blindly right;

Though learn’d, well-bred; and though well-bred, sincere;

Modestly bold, and humanly severe?

Who to a friend his faults can freely show,

And gladly praise the merit of a foe?

Blest with a taste exact, yet unconfin’d;

A knowledge both of books and human kind;

Gen’rous converse; a soul exempt from pride;

And love to praise, with reason on his side?

Such once were critics; such the happy few,

Athens and Rome in better ages knew.

The mighty Stagirite first left the shore,

Spread all his sails, and durst the deeps explore:

He steer’d securely, and discover’d far,

Led by the light of the Mæonian Star.

Poets, a race long unconfin’d and free,

Still fond and proud of savage liberty,

Receiv’d his laws; and stood convinc’d ’twas fit,

Who conquer’d nature, should preside o’er wit.

Horace still charms with graceful negligence,

And without methods talks us into sense,

Will, like a friend, familiarly convey

The truest notions in the easiest way.

He, who supreme in judgment, as in wit,

Might boldly censure, as he boldly writ,

Yet judg’d with coolness, though he sung with fire;

His precepts teach but what his works inspire.

Our critics take a contrary extreme,

They judge with fury, but they write with fle’me:

Nor suffers Horace more in wrong translations

By wits, than critics in as wrong quotations.

See Dionysius Homer’s thoughts refine,

And call new beauties forth from ev’ry line!

Fancy and art in gay Petronius please,

The scholar’s learning, with the courtier’s ease.

In grave Quintilian’s copious work we find

The justest rules, and clearest method join’d;

Thus useful arms in magazines we place,

All rang’d in order, and dispos’d with grace,

But less to please the eye, than arm the hand,

Still fit for use, and ready at command.

Thee, bold Longinus! all the Nine inspire,

And bless their critic with a poet’s fire.

An ardent judge, who zealous in his trust,

With warmth gives sentence, yet is always just;

Whose own example strengthens all his laws;

And is himself that great sublime he draws.

Thus long succeeding critics justly reign’d,

Licence repress’d, and useful laws ordain’d;

Learning and Rome alike in empire grew,

And arts still follow’d where her eagles flew;

From the same foes, at last, both felt their doom,

And the same age saw learning fall, and Rome.

With tyranny, then superstition join’d,

As that the body, this enslav’d the mind;

Much was believ’d, but little understood,

And to be dull was constru’d to be good;

A second deluge learning thus o’er-run,

And the monks finish’d what the Goths begun.

At length Erasmus, that great, injur’d name,

(The glory of the priesthood, and the shame!)

Stemm’d the wild torrent of a barb’rous age,

And drove those holy Vandals off the stage.

But see! each Muse, in Leo’s golden days,

Starts from her trance, and trims her wither’d bays!

Rome’s ancient genius, o’er its ruins spread,

Shakes off the dust, and rears his rev’rend head!

Then sculpture and her sister-arts revive;

Stones leap’d to form, and rocks began to live;

With sweeter notes each rising temple rung;

A Raphael painted, and a Vida sung.

Immortal Vida! on whose honour’d brow

The poet’s bays and critic’s ivy grow:

Cremona now shall ever boast thy name,

As next in place to Mantua, next in fame!

But soon by impious arms from Latium chas’d,

Their ancient bounds the banished Muses pass’d;

Thence arts o’er all the northern world advance;

But critic-learning flourish’d most in France.

The rules a nation born to serve, obeys,

And Boileau still in right of Horace sways.

But we, brave Britons, foreign laws despis’d,

And kept unconquer’d, and uncivilis’d,

Fierce for the liberties of wit, and bold,

We still defied the Romans, as of old.

Yet some there were, among the sounder few

Of those who less presum’d, and better knew,

Who durst assert the juster ancient cause,

And here restor’d wit’s fundamental laws.

Such was the Muse, whose rules and practice tell

“Nature’s chief master-piece is writing well.”

Such was Roscommon — not more learn’d than good,

With manners gen’rous as his noble blood;

To him the wit of Greece and Rome was known,

And ev’ry author’s merit, but his own.

Such late was Walsh — the Muse’s judge and friend,

Who justly knew to blame or to commend;

To failings mild, but zealous for desert;

The clearest head, and the sincerest heart.

This humble praise, lamented shade! receive,

This praise at least a grateful Muse may give:

The Muse, whose early voice you taught to sing,

Prescrib’d her heights, and prun’d her tender wing,

(Her guide now lost) no more attempts to rise,

But in low numbers short excursions tries:

Content, if hence th’ unlearn’d their wants may view,

The learn’d reflect on what before they knew:

Careless of censure, nor too fond of fame,

Still pleas’d to praise, yet not afraid to blame,

Averse alike to flatter, or offend,

Not free from faults, nor yet too vain to mend.

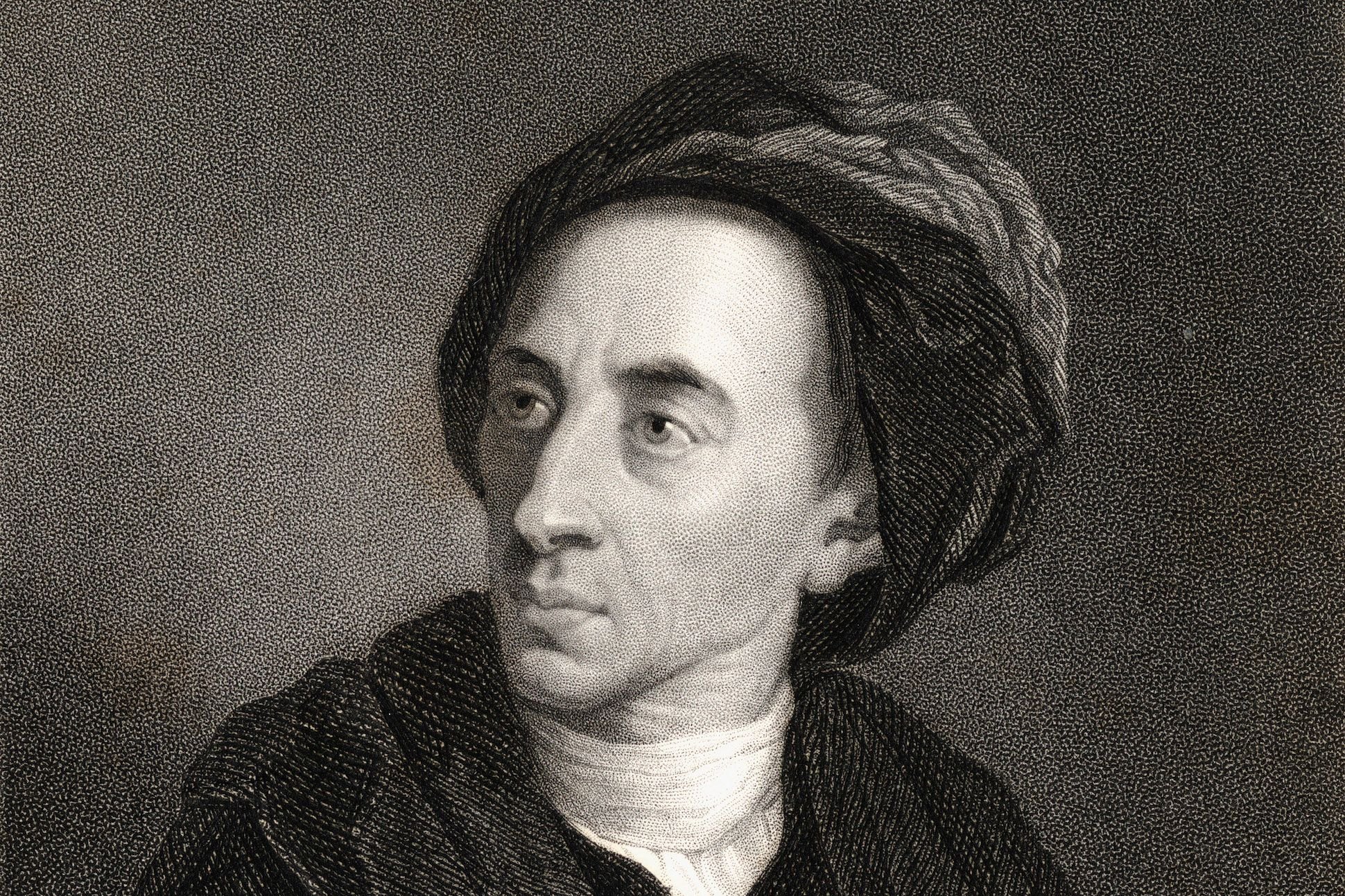

The acknowledged master of the heroic couplet and one of the primary tastemakers of the Augustan age, British writer Alexander Pope was a central figure in the Neoclassical movement of the early 18th century. He is known for having perfected the rhymed couplet form of his idol, John Dryden, and turned it to satiric and philosophical purposes.